Daniel commented about the lack of photos in my last post. He was right – to paraphrase a boss I once worked for – “Too many words, not enough graphics.” Okay, here’s a recent photo of Donna’s raised vegetable garden.

This is a shot of the worm bin in the raised garden bed. When I feed the worms, I bury the kitchen scraps along with some used coffee grounds, ground egg shells and shredded cardboard. The used coffee filter is there to mark where I last buried the feed – it will eventually break down and be consumed just like the cardboard.

When I fluffed the soil and fed that bin yesterday, every handful of soil had dozens of juvenile worms. I have no doubt the population in this bed exceeds 1,000 worms now and it keeps growing.

I also mentioned the external worm bin I created out of fabric garden pots.

I started with 600 red wigglers in this bin. It’s about five weeks behind the in-garden bin, but I saw several worms yesterday that appeared to be ready to drop cocoons. I think a population explosion is about to erupt in this bin.

Look closely and you can see a few worms lounging on the surface. Worms do not like sunlight – red wigglers usually hang around below the surface to a depth of six to eight inches. In another month or two I expect to start sifting a pound or more of worm casting garden fertilzer from this bin weekly.

I started discussing astrophotography equipment in my last post. Astronomy can be as simple as looking up at night and maybe sketching the constellations – or maybe using binoculars to look at the moon or planets. Once you get a proper telescope, there are many paths you might want to follow. Photographing the night sky can become a long, winding road with many potential potholes and expenses along the way.

Once I went down this rabbit hole, there was no turning back. The sky is the limit when it comes to equipment and costs. It doesn’t have to be super expensive, but be aware – it ain’t gonna be cheap!

The mount for your telescope is arguably the most important piece of equipment. It needs to be very solid, reliable and have the ability to track the apparent movement of the celestial objects. This is not too difficult with the moon or planets – they are large, bright objects and can be followed fairly easily with a simple altitude-azimuth type mount. You may have to make periodic manual corrections after a few minutes of tracking.

If you want to image deep sky objects (DSO) like star clusters, galaxies or nebulae, you need a more sophisticated mount. A German equatorial mount (GEM) is most often used. This type of mount needs to precisely aligned with the celestial pole – north pole in the northern hemisphere. This type of mount tracks in two directions, one called Right Ascension (RA) and the other is Declination. This allows the mount to compensate for the rotation of the earth as it tracks the apparent movement of objects in the sky. Stars appear to “rise” in the east and “set” in the west. In reality, they only appear that way due to the earth’s rotation. Additionally, their position in the sky will be different as the earth revolves around the sun, making seasonal star charts necessary.

I have a SkyWatcher HEQ5 Pro GEM mount. It has two electric stepper motors to adjust RA and declination respectively. It has an onboard control unit to point at objects in the night sky and track them. This works okay – it’s more than good enough for planets and the moon – but it requires some manual correction. It comes with a hand controller to direct the mount. To use this, I fitted my telescopes with a red dot aiming device that I aligned precisely with the telescope. That way, I could easily find the desired object in the red dot non-magnifying lens, then fine tune the telescope position. It’s a big sky up there and it’s easy to get lost trying to find an object through the small field of view of a telescope.

Trying to find and track DSO targets is much more difficult. In the light pollution found in any populated area, many targets cannot be seen with the naked eye. A red dot device is useless if you can’t even see the object. Upgrades are needed.

First, I ditched the hand controller and I bypassed the onboard control unit of my mount. I now control it with a laptop, ASCOM drivers and different software. I have a program called Cartes du Ciel (French for Sky Chart) that I use to find my target. The target coordinates are then imported to a program called NINA (nightime imaging and astronomy – think of the second “N” as an acronym for “and”, like Guns’N’Roses). NINA is my main software and it directs everything else. I set up a sequence in NINA and it connects to Cartes du Ciel, then activates a program called EQMod to control the mount and another program called PHD2 that handles the tracking calculations. Once these programs are properly configured and working together, I can get the ball rolling with a few key strokes.

But, it’s not so simple. Now, instead of a red dot finder, I have a guide scope mounted on the telescope. The guide scope is a mini-telescope, the one I use is an Altair 60mm ‘scope with a focal length of 225mm. I have a ZWO brand ASI120MM mini-camera on it. This ‘scope doesn’t need to be precisely aligned with the main telescope as long as it is rigidly mounted and moves with the main telescope tube with minimal flexure.

The mini-camera is connected to my laptop and PHD2 uses this camera to identifiy stars. I run through a calibration sequence that allows PHD2 to “learn” how to keep a target centered in the frame. This can take up to 30 minutes to complete. Once that calibration is done, I start NINA and it points the telescope to the target I imported from Cartes du Ciel. Once on target, PHD2 identifies up to nine nearby stars and “learns” where in the sky we are pointing. It tracks those stars to keep them in position in the guidescope, thus the main ‘scope stays in proper position to track the target. Through EQMod, it will send tiny pulses of electricity to the mount stepper motors to keep the ‘scope on target. It’s pretty amazing.

Once this is accomplished, NINA starts the imaging process. Deep Sky Objects are very far away and usually faint – if you can see them with the naked eye or even binoculars, they look like cloudy smudges in space. To resolve them into a usable imge, it takes a lot of time to collect enough light photons emitted by the object onto the camera sensor. We need long exposures usually taking anywhere from 30 seconds to 10 minutes or more. This is why precise guiding is necessary. If we don’t remain aligned with the target, the apparent movement of stars across the sky from the earth’s rotation will make the stars turn from pinpoints into streaks across the image.

The next issue that arises with long exposure time is heat generated by the electronic sensor. As it heats up, anomolies start appearing – some hot pixels will develop and white spots can appear in what should be a dark area or color shifts will randomly appear. To avoid this, DSO cameras use thermo-electric cooling (TEC). This is usually done with a Peltier cooling device – it doesn’t use any gases or fluids, it totally electronic. My ZWO ASI533MC Pro camera has this type of cooling and I run it at 10 degrees fahrenheit. NINA monitors the sensor temperature and controls the TEC to maintain that temperature.

Planetary or lunar imaging is so simple by comparison, but it has its challenges as well. It took me about three months of continuous improvement before I had an image of Jupiter that I was satisfied with – it’s my header image for this blog now. I expect DSO to take at least a year before I can start recording useful images.

Friday night was the first time I got everything working as it should – all of the software calibrated and communicated together and the ‘scope found a target I couldn’t even see. I programmed a sequence of 50 exposures at 90 seconds each. In between each exposure, the software did something called dithering. This is where PHD2 moves the telescope a miniscule distance – the image shifts on the camera sensor by a few microns. This small movement allows correction of any hot pixels in the process, as they don’t continuously appear in the exact same spot of every frame. PHD2 then waits several seconds to make sure there’s no residual vibration in the ‘scope from the tiny movement, then it takes the next exposure. Some guys will run their ‘scope all night long to get the maximum amount of exposures to process into an image.

Processing the data acquired through the digital camera sensor requires another suite of software and it’s a whole ‘nother learning experience. I won’t get into that now, as I’m just beginning to learn.

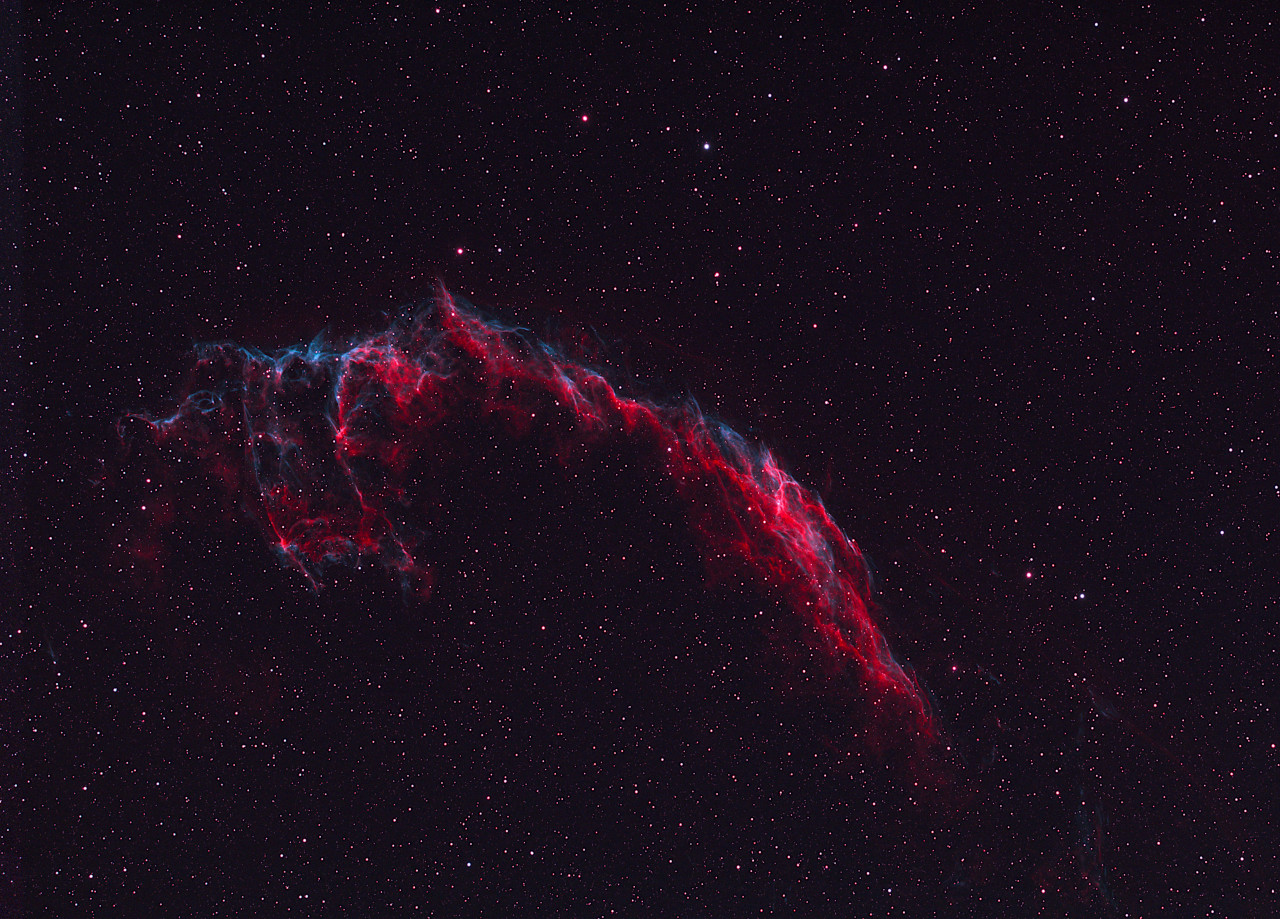

Unfortunately, on Friday night, I wanted to check the status of my Bluetti power supply after a couple of hours. It provides portable power – 120-volt AC for my laptop. 12-volt DC for the ASI533MC cooled camera and several 5-volt DC USB ports. I pressed the wrong button and it cut off power, shutting my camera and USB connections off and killing my session after 23 of the planned 50 frames were shot. I was happy that I had everything working right up that point, but the lack of frames and exposure time meant the resulting image was poor. It lacked color and detail, but I felt like I made a big step forward and it will only get better from this point.

If the forecast holds true, I think I’ll head out on Thursday or Friday to the Weaver’s Needle Viewpoint and try another shot at DSO from a darker area. I think I’ll use my AT 115EDT instead of the WO Z73 telescope. I have quick release mounts on both telescopes so I can switch the guide ‘scope and camera between them instead duplicating equipment.

I’m making progress on another front. It’s been three weeks since my gall bladder surgery and I’ve regained a lot of strength and stamina. The surgeon, Dr. Garner, warned me against doing anything strenuous or heavy lifting for four weeks. He said “Don’t do anything that makes you constrict your core or grunt.” I’m taking heed of that warning. Donna is helping me keep my strength up with her usual delicious, nutricious culinary skills.

Here is a rice bowl with salmon, cabbage, nori, cucumber and avocado drizzled with a sesame marinade as presented.

And here it is with everything tossed.

Fresh collard greens from the garden.

Collard greens saute in olive oil with garlic, chicken broth and apple cider vinegar. Served with grilled shrimp with chile and garlic and cheesy grits.

We’re looking forward to a visit from Alana and Kevin – they’re coming down from Washington next weekend. In March, my daughter Shauna, her husband Gabe and my granddaughter Petra will visit from Bermuda.

Hopefully, next time I’ll have a better DSO image to share.

Edit: After playing around with Astro Pixel Processor I was able to slightly improve the Andromeda image.